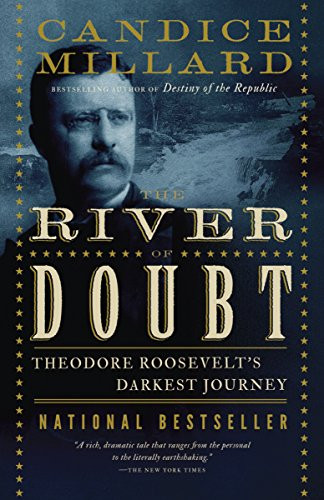

Candice Millard impressed our group before as an historian and as a storyteller – see our earlier review of Destiny of the Republic. This book repeats those skills and adds naturalist to our accolades.

Millard first introduces us to Theodore Roosevelt after his defeat for the presidency in 1912. After two terms as president, Roosevelt had selected William Howard Taft as his successor, but during Taft’s term they had a falling out and TR tried to unseat Taft in the 1912 election. In the end, they both lost to Woodrow Wilson. As he had done after the death of his first wife and after other disappointments, Roosevelt began looking for an adventure to make up for the loss. He seized on the idea of an Amazonian exploration. Both the North and South Poles had recently been explored, and the major rivers of Africa had been mapped; the Amazon was still largely unexplored. He outlined a speaking tour of South America with a river expedition to follow, descending a previously explored river that joined the Amazon. While Roosevelt was planning the speaking tour, various hangers-on planned and equipped the expedition for that route, though with little information on which to base their provisioning.

Filling in the map of interior Brazil was an ongoing challenge to its government, and the task was primarily entrusted to the Telegraph Commission, headed by Colonel Cândido Rondon, an army officer whose career mission was explore the Amazon Basin and to peacefully meet the indigenous inhabitants of the region. As luck would have it, Rondon was assigned to accompany and guide Roosevelt’s expedition. To further his own interests, Rondon preferred a route that would explore new country, and Roosevelt welcomed the adventure of new discovery. The River of Doubt met both men’s purposes. It was a river that was presumed to run hundreds of miles across the Amazon rain forest, but as of 1913, it remained unexplored and unmapped. Its source and outlet were known, but its course was a matter of doubt.

The expedition shifted to the River of Doubt, and it entered the unknown in February 1914.

What they passed through was Amazonian rain forest, a terrain for which they were remarkably unprepared. Here the naturalist part of Millard’s skill comes alive. She explains how the rain forest looks and feels, how it evolved, and importantly why the expedition was not able to forage food there. The rain forest had evolved highly specialized plants and animals that disperse themselves over wide regions and in unfamiliar ways. Animals and fruit are often at tree-top level and camouflaged so that the American and even the Brazilians could not spot anything, hunt anything, or harvest anything. Their crates of provisions, with rations of white wine and mustard, provided little nutrition but were a weighty hindrance at every one of the portages around the frequent rapids and waterfalls of the river. The expedition began on short rations, and since foraging was unsuccessful, time became the measure of their danger.

The expedition met a succession of native tribes, especially the Cinta Larga, who tracked them while remaining almost invisible. Remarkably, the tribes let the expedition pass without attack, not perceiving them as an actual threat. Given Rondon’s steadfast insistence on peaceful dealings, that judgment proved right, at least as to this expedition. The only deaths of the expedition were due to river accidents and a murder. (But in the long run, the fate of South American tribes was not much better than their North American counterparts).

Roosevelt’s ambition for adventure was more than satisfied. The expedition was out of touch with the rest of the world for about eight weeks. It was poorly equipped for what it confronted. The boats they took to Brazil were completely unsuitable, and the expedition ended up using hollow-log canoes with very shallow draft that were difficult to bring through rapids and were extremely heavy to portage. It lost half of those canoes and had to hollow out new ones at the cost of time and labor. The labor, of course, was initially performed by Brazilian camaradas, but soon the American and Brazilian officers were laboring alongside them. Rations were short to begin with, quickly diminished through accidents, and to the extreme disappointment of the Americans could not be supplemented by hunting. The rain forest proved as inhospitable as any adventurer could want. It was hot, buggy, and – surprise – rainy. Portaging the frequent rapids and falls ate up time and energy and invited accidents. The river contained piranhas and other deadly fish, along with parasites and disease. On land, the expedition was open to attack by unseen Indians and snakes. Insects brought constant misery and disease. Most of the expedition suffered from malaria, especially Roosevelt’s son Kermit, who had joined the expedition to protect his father. TR had a seriously infected leg injury that brought him near death. At one point he talked with Kermit about leaving him behind. Millard uses diaries and letters to give first-hand accounts of the desperation the expedition felt. It finally approached the Amazon and met rubber harvesters and the army unit that awaited them at the edge of civilization.

The book gave us a wealth of subjects for discussion. Most of us have crossed an Amazonian expedition off our bucket lists. The expedition was rife with the sense of cultural superiority common to explorers of that period, such as the reluctance to seek out local advice on such basics as food and boats. Millard gives great insights into the always fascinating characters of the Roosevelt family. While we are not planning Amazonian travel, we would be happy to read more of Millard’s work.

— Bill Smith