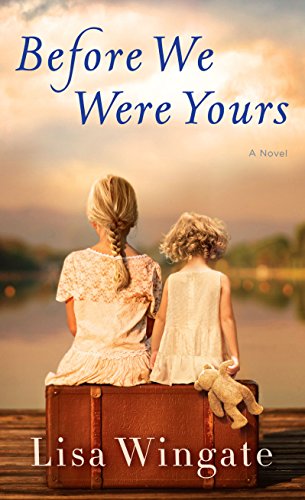

This novel is based on true events that actually boggle the mind of the modern reader. Georgia Tann was a prominent maven of Tennessee society who sought to better society through the adoption of poor, underprivileged children into wealthy socially-advantaged families. Operating during the distressed times of the 1930s Depression, she established the Tennessee Children’s Home Society which operated orphanages across Tennessee and Georgia. That good intention went badly awry, however, and many of the children who ended up in these orphanages were never actually given up for adoption by their birth families. Some were snatched up on their way home from school. Others were taken from parents who were conned into signing away their parental rights by promises that their children would be returned when the family could get back on their feet. When the parents tried to reclaim their children, adoptions had been finalized, names changed, and records sealed. All of that is true and it is a grisly story that continued for more than a decade.

Against this history, Wingate structures her novel in two voices. The voice of 12-year-old Rill in Memphis, Tennessee, in 1939 alternates with that of Avery, a 30-something daughter of wealth and privilege in modern-day Aiken, South Carolina. Rill’s story moves us forward in time. Avery’s story ultimately unravels backward through the unsuspected secrets of her family,

Rill is the oldest of five children who were taken from their family’s vagabond houseboat on the Mississippi River when their father takes their mother to the hospital. Her story and the story of her siblings unfolds over a three-month period in alternating chapters of the book as Rill, rechristened May in the orphanage, fights to keep her sisters and brother with her.

In the interwoven story, Avery encounters a woman, May, in a nursing home who grabs her wrist and takes a bracelet that was given to Avery by her grandmother. Avery’s grandmother is in the dementia unit of a different nursing home. As Avery retrieves her bracelet, she begins to talk with May and sees a photograph that looks suspiciously like one that her grandmother has.

We see where this is going. And it does go there, at a fast tempo, and with some riveting scenes and phrases (such as fans trying to move humid summer air that has no desire to be moved).

Our book club mostly enjoyed reading this book and it is indeed a good tale. However, many thought the “Avery” story was too pat, too romance-novel-ish and used unnecessarily stereotyped characters, particularly Avery’s fiancé and the man who helps her unravel her family’s past. Our discussions of the book mostly centered around the character of Rill and her mighty efforts to save her siblings and their memories of their “real” parents; and around Georgia Tann, who died before she could be charged with the crimes she committed; and around our society’s changing views about adoption. The book did push us to consider what we might have done in the circumstances that confronted families in abject poverty during the Depression. What might we have done to save our children? The scene where a father comes to the orphanage to reclaim his children and is told that they are already gone “to a better life,” is riveting.

— Review by Jeanie and Bill Smith