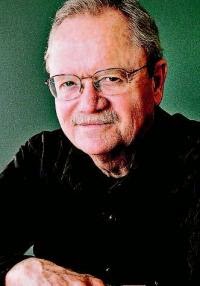

The other morning over coffee and The New York Times, my husband said, “Did you read Kent Haruf died?” I hadn’t, but I wasn’t surprised. I understood his most recent novel, Benediction, was given that title for a reason.

He is one of the few prolific writers of whom I can say that I’ve read all his books. And I’m sorry there will be no more. But I’d love to read at least one again (Plainsong would be my preference) and discuss it with the BB&Bers. (Also, it would address Ken’s lament that we’ve been reading a disproportionate number of women authors lately. ) 🙂

He is one of the few prolific writers of whom I can say that I’ve read all his books. And I’m sorry there will be no more. But I’d love to read at least one again (Plainsong would be my preference) and discuss it with the BB&Bers. (Also, it would address Ken’s lament that we’ve been reading a disproportionate number of women authors lately. ) 🙂

Plainsong was a finalist for the 1999 National Book Award. In it, as in all his novels, the style is unadorned; he lets his characters show themselves on the page by what they do and say; we have to get to the bottom of things on our own by observing their behaviors and thinking about them. He is very much a writer of place: of small town and rural Colorado. The characters are exactly life sized. They are ordinary people: elderly bachelor brothers on a cattle ranch; a pregnant teenager; a lonely and well-intentioned high school teacher; a single-parent dad; two little boys whose mother suffers from depression. It’s in their response to each other that Haruf shows us grace in the most unlikely places.

Even if it doesn’t make it onto our official reading list, I highly recommend it to you fiction lovers. And if you read it, I’d like to hear your impressions.

—Sharelle Moranville