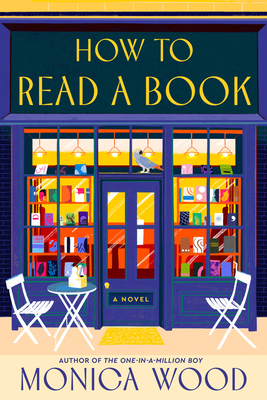

The cover of Monica Wood’s How to Read a Book is warm and inviting, especially to a lover of books and reading. It shows the exterior of a cozy bookstore from the sidewalk, beckoning readers to come on in. What follows is a highly engaging and uplifting story full of quirky and complex characters, difficult situations, emotional highs and lows, growth and redemption, and resilience. Is there a bookstore in the novel? Yes – but there’s so much more!

There’s Harriett, a.k.a. “Bookie,” who runs a book club inside a women’s prison in Maine. She is dedicated to sharing the power of literature with every member of the group, helping them know their worth and express their feelings as they read aloud, react, discuss, write, and make connections to themselves and others. Wood does not sugar-coat their voices as they express powerlessness, rage, longing, resentment, distrust, love and more. We get to know each member of the group as they support one another through a very meager existence.

But if the cover of the book showed a prison, it would not suggest that one of the youngest inmates, 22-year-old-Violet, is suddenly freed at the beginning of the book. In fact, the bulk of the story is arguably hers as she tries to navigate life as an ex-con “on the outs” where she never had a chance to live independently before being locked up. We watch as she goes from a tense reunion with her sister to a chance meeting with Harriett (at the bookstore!) and another fraught reunion with Frank, the husband of the woman she killed in the drunk driving accident that landed her in prison. Through much effort she lands a job for which she has “affinity,” a word that provides fledgling self-esteem, documenting research on talking parrots in a university lab – where the birds themselves are characters, as well as her ill-tempered, manipulative boss.

Perhaps a bird would have made a good cover image, since the birds, too, were captives. And in addition to Violet’s work with the birds, the inmates give a gift of a small, knitted bird to Harriett as a token of their appreciation. She keeps it, though she’s been warned not to accept anything from them, and not without consequence. This repetition of birds seems symbolic, and yet a bird on the cover wouldn’t adequately represent Frank, a third major character who longs for a relationship with Harriett while feeling terrible about his true feelings around the death of his wife. No spoilers, but it’s not what you’d think. In addition, we get to see his rocky relationship with his daughter and his brilliance as a retired machinist-turned-handyman….at the bookstore.

So, maybe the bookstore is the thing that ties everything together and is the best choice for the cover after all. As a member of our group observed, avid readers are drawn to books that have bookstores on the cover, and an avid reader would thoroughly enjoy this book. Also, its marketing had the intended effect. It looked like it would be an easy and enjoyable read, and it was, while still being intricately well-written.

As a bonus, our book club happens to include several people who have spent time volunteering at a women’s prison in Mitchellville, Iowa, as well as providing support to women who have recently been released. While there are some differences between the systems in Iowa and Maine, and it’s clear that some details were added to advance the story (such as Violet being outfitted with a fully stocked apartment upon her release – a lucky break that is very unlikely in reality), their general take was that the overall tone of the prison aspect of this book was spot-on. If any Iowa area readers are so inspired, check out Women at the Well for ways to get involved with helping women who are incarcerated and recently released.

We were glad to have found and read this book, and glad that it left us feeling hopeful. It was also a good reminder of this:

“The line between this and that, you and her, us and them. The line is thin.”

— Julie Feirer