Category: Non-Fiction Reviews

The Wright Brothers and The Brothers Vonnegut

I have been reading two books, both about brothers, strangely enough.

First, I checked out an audio version of The Wright Brothers, David McCullough’s latest book, his tenth. The two-time Pulitzer Prize winner tells the dramatic American story of Wilbur and Orville Wright. Most of us are likely knowledgeable about their first flight at Kitty Hawk on the outer banks of North Carolina on December 17, 1903, changing history forever. Kitty Hawk was selected for their flight experiments because it offered ideal weather, seclusion, and soft places to land in the sand. But what most of us don’t know that what happened after Kitty Hawk is the most unlikely part of their story.

Shockingly, although they made more than 150 flights afterward, their achievement drew almost no notice until 1906, when they were issued patents for the Wright Flying Machine. Even then, when their Congressman helped them approach the War Department, they were met with yawns. The Wright’s, who ran a bicycle ship on Dayton, Ohio, had to go to France to find substantial support for their invention.

As in his earlier books about Harry Truman, John Adams and Theodore Roosevelt, McCullough hones in on his subjects’ boundless capacity to educate themselves. Far more than a couple of unschooled bicycle mechanics, they were men of exceptional courage and determination, and of far-reaching intellectual interests, much of which they attributed to their upbringing. Every member of the Wright family was an avid reader. The personal library of their father, a cleric bishop, included works of virtually all the popular authors of the time, as well as two full sets of encyclopedias.

McCullough relates how their efforts led them to determine the proper shape of the wing, the correct angle into the wind, and how to compensate for the weight of the engine. They crafted a sophisticated wind tunnel and created an innovative propeller. When no automobile manufacturer would supply them with a suitable motor, they collaborated with a local mechanic to design their own.

McCullough also discusses their private family life, including that the two brothers never married and were seldom apart. And writes a lot about their sister Katherine, the most important woman in their life. Her steadfast devotion to her brilliant brothers were of great assistance to their success.

It wasn’t until the spring of 1908 that the Wright’s were able to capture the imagination of their own country, when they held a number of flight exhibitions for the press and the military. This led to their ability to sell their patents for a great deal of money, and made them internationally famous. In summary, it is a story well told, about what might be the most astonishing engineering feat mankind has ever accomplished.

Then, for Christmas, I received a copy of The Brothers Vonnegut, by Ginger Strand. Kurt Vonnegut has always been one of my favorite authors and I believe I’ve read every book he published, as well as many of his short stories., so was most pleased to dig in on this story.

Bernard Vonnegut was eight years older than brother Kurt, and for decades was far more successful. Interested in science from an early age, he earned a Ph. D. in chemistry at MIT in 1939, and when the US entered WWII, he was recruited by the Army to devise better ways to de-ice bombers. Meanwhile, Kurt joined the Army and was captured by Germans during the Battle of the Bulge, and as a prisoner witnessed the Allied firebombing of Dresden, the event that later inspired his most famous novel, Slaughterhouse-Five

In 1947, soon after he returned home from the war, Kurt went back to college and tried unsuccessfully to publish short stories. Desperate to earn a living for his family, he quit school and accepted a job in the publicity department at General Electric. At the time, GE was a very prosperous company with sales then more than double during the peak of the war years, and had become synonymous with postwar prosperity.

When Kurt arrived, some of the nation’s finest minds were then focused on climate change, and his brother Bernard had been working on one of GE’s most high-profile projects – weather modification. Other scientists at the famed GE Research Laboratory had figured out that dumping dry ice into clouds would produce snow or rain. It was Bernard himself that found that silver iodide had an even more durable effect on cloud seeding. It was questionable as to how this new ability to control the weather would affect warfare, and the military took control of the experiments titled Project Cirrus.

“Progress is our most important product”, the company proclaimed, a motto that both Vonneguts came to question. Optimistic about America’s future when they first joined GE, the brothers both became increasingly pessimistic after they realized that manipulating the weather was seen as a potential war weapon.

The book is partly an account of both brothers’ work at GE and partly a study of how GE’s scientific research became themes in Kurt’s fiction. Some of the weather experiments worked, and some worked too well, causing floods that spawned lawsuits against GE. These experiments inspired the military which hoped to use rain as a weapon of war – creating floods and tidal waves, which appalled both Vonnegut brothers.

The book is not a biography of the brothers, but rather focuses almost exclusively on their years at GE and how Bernie pressed for government oversight and how GE influenced Kurt’s fiction. His first novel, Player Piano in 1952 and his fourth, Cat’s Cradle in 1963, include satirical portraits of a company much like GE. He loathed the policy of nuclear deterrence, advocated disarmament, and didn’t think scientists had much business doing research that could only conceivably cause harm. He didn’t hold out much hope for us in Fates Worse than Death, when he wrote “My guess is that we really will blow up everything by and by”.

Well, although we haven’t blown us up yet, we still continue to mess with the weather.

Two great books about two brothers. Well worth the reading.

— Ken Johnson

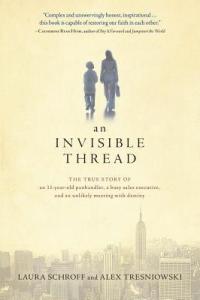

An Invisible Thread, by Laura Schroff

In this true story, Laura Schroff befriends a homeless boy, Maurice, and he gradually becomes central to her life. We asked whether we would have had the courage to act as Laura did. We acknowledged that we would have considered the “what if”s and “why”s and “oh no”s of bringing such a boy—and his family— into our lives. Schroff did it with only minimal hesitation and with a wholehearted welcome, and she faced a stunning learning curve she shares with the reader.

Maurice lives within feet of Laura’s comfortable apartment in midtown Manhattan, but they might as well have been in different countries. Laura even has to teach Maurice how to blow his nose because he has never done it, and she ends up making him school lunches in a plain brown paper bag so he can fit in with the kids at school.

Laura is honest about how her relationship with Maurice eventually foundered as she tried to build a life with a new husband, and her backstory helps explain why she might have taken the chances she did with Maurice and also defines her need to have a child of her own.

The writing is a bit weak—Schroff wrote the book with friend and colleague Alex Tresniowski, which may have reduced some of the immediacy and power of the memoir. It is an easy read, though.

—Pat Prijatel