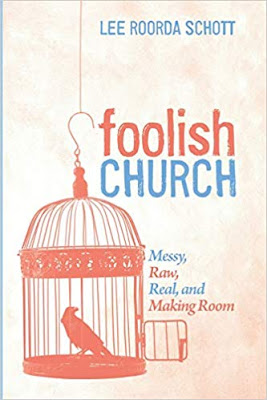

Pastor Lee visited with the Books, Brews, and Banter group this April. We talked about her inspiring book and how we might apply her wisdom to our own lives. Below are three individual reviews of her book, which are also posted on Amazon’s page for the book.

This powerful book is somewhat scholarship (footnotes and an extensive bibliography), somewhat how-to (discussion questions at the end of each chapter, plus helpful, practical appendices), and somewhat a memoir of Pastor Lee Roorda Schoot’s leading a church inside a women’s prison. But most of all, it’s a passionate argument to make our churches really real—not just shiny, happy places where the nice people go periodically.

In a well-paced, anecdotal style, Pastor Lee convinces the reader (at least this reader) that if we open our churches (with wise and necessary boundaries) to ex-offenders, we also open our hearts and minds in a way that benefits each of us and the whole community. FOOLISH CHURCH: MESSY, RAW, REAL, AND MAKING ROOM isn’t just a book about welcoming ex-offenders. It’s a book about welcoming ourselves and the worst things we have ever done. About acknowledging life’s messiness. And making room.

—Sharelle Moranville

“Pastor Lee,” as the inmates at the Iowa Correctional Facility for Women at Mitchellville call her, gets down to the raw and messy sides of being part of a church today. Are we welcoming? Inclusive? Judgmental? Do we accept one another’s scars (and our own), or are we looking for a sanitized community that’s an idealized version of ourselves? In clear, direct and inspirational prose, Schott shows us the way to the church community we could be, using her relationship with women inmates as a model. A book well worth reading for any faith community.

— Pat Prijatel

Foolish Church is a relatively short book that is long on wisdom about how to build more caring communities with room for people the church has often overlooked. Her message is a powerful, yet simple message that applies to all of us. It is a plea to move beyond an assembly of the upright and proper, to make room for those on the edges of respectability.

One quote that really resonates is “how do we become churches that build boundaries, but not walls.” Are we welcoming, inclusive, judgmental, or looking for a sanitized community? I believe that those are also questions that should be heeded by our President in making our country one that builds boundaries, not walls.

—Ken Johnson